Last week I attended a course at PSTA focused on painting trees and flowers in the Persian miniature style. Partly because its been a while since I painted anything and feel I need the practice, and partly as a treat for myself, because why not hey!

The course was taught by Farkhondeh Ahmadzadeh, an extremely talented artist and all round lovely person, and with focus on two of my favourite things in this world, it was great timing as all the trees were in full blossom, and inspiration was physically growing around us. Held at PSTA as part of their Open Programme, it felt like I was back at uni, back in class during the first year of my MA! But this time with more confidence and more self assurance.

The course opened with a presentation introducing the genre and style of painting, and the principles of nature in traditional Persian miniatures. The depiction of the natural world is there to remind the reader (as these paintings would form mart of the illustrations and illuminations of manuscripts) that there is a paradise. The representation of flowers, plants, trees and fruit, whilst inspired by the world around us, have an other worldly quality, and an almost fantastical feeling about them. The vegetation doesn't have to be related, for example it is perfectly acceptable to have some spring blossom neighbouring an autumnal tree. Its about fantasy and paradise, and your fantasy and your paradise, all whilst remaining somewhat loyal to the inspiration.

Likewise, proportions and perspective are given the same treatment. Persian miniatures are always painted in the plain/flat perspective, and are never realistic or dimensional. The reason for this is because God, or The Source, has no dimensions, and is limitless. Therefore the less dimensions we have, the closer we are to The Source. The perspective, proportions and forms within the painting could also be symbolic, emphasising a particular part of the narrative or message of the story.

The painting process itself starts off with preparing the paper. It is sized with hollyhock flower (purple or white) and sometimes egg white, and then burnished. This fills the pores in the paper and allows the pigments to sit on the surface and not be absorbed. Once dry it is stained so give the ground some warmth and depth. This could be done using the water from boiled pomegranate skins, tea, saff flower, and many more, and the paper is burnished again.

Pigments are ground from, depending on the colour, rocks and minerals, earth, plants, soot, and even animal parts. Brushes are made from the softest kitten hair (without harming the kitten) as they hold the pigment and are of the right length. Once the design and composition has been decided on, it is drawn up and traced onto tracing paper, which is retraced or burnished onto the paper to be painted.

The painting then begins, and colour is applied in layers. We start off with the background block colour, and once dry, add in the small details. This is done with a dry brush technique, and the rendering entices a play with light and shade. In Farsi this is called the pardakht technique. A small area can take many hours to render, so patience and practice really is a virtue!

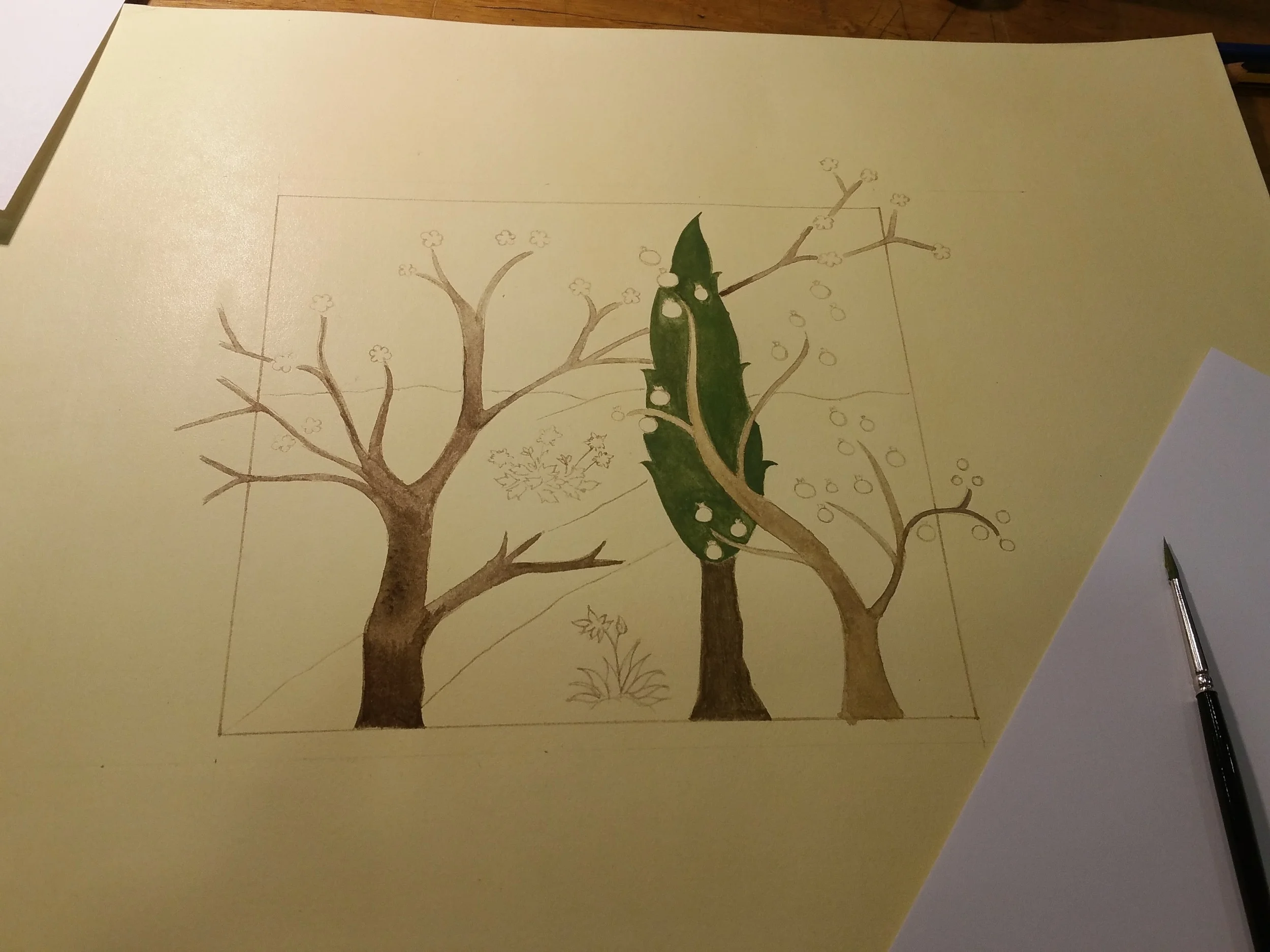

Here you can see some pictures of my progress (and more on my Instagram). I'm going to try my best to finish this painting when I get some quiet time. Painting all those tiny leaves and petals may seem tedious, but with the right mindset, can turn into quite meditative process. Its something that requires a lot of concentration and being in the moment. So all these colouring books and mindfulness stuff...yep the Persians have been doing that for centuries!